FRISCO, TEXAS – It’s no secret that the zoning system in the U.S. as we know it is different compared to European and Asian countries’ zoning systems. This is particularly the case for suburbs. When one thinks of American suburbs, white picket fences, lush, freshly mowed lawns, and rows upon rows of cookie-cutter houses are what come to mind. Suburbs also have a heavy reliance on cars, resulting in car-dependent suburban landscapes, a lack of car-free spaces, and other issues. Suburban America is in need of a long overdue facelift.

Lee Anne Fennel, a legal scholar, refers to exclusionary zoning as “a central organizing feature in American metropolitan life.” And her description couldn’t be any more true. Zoning as we know it in America is fundamentally flawed.

In order to explore this concept of zoning further, we need to begin by defining what zoning is. According to Merriam-Webster, zoning is the act or process of partitioning a city, town, or borough into zones reserved for different purposes. So, in essence, zoning allows for cities to establish their own rules on how industry, residences, commercial spaces, etc. are organized in terms of land use and what types of restrictions are placed on each zone in terms of what can and can’t be built and rules surrounding these regulations.

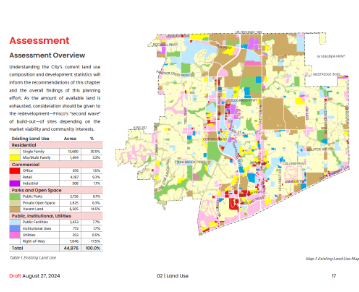

American zoning follows a pattern of zoning known as Euclidean zoning, where industry, commercial, residential zones, etc. are all classified into their own separate zones without allowing any mixing of zones.

In many cities across America, an overwhelming majority of cities are built with car dependency and single-family homes in mind. Wide streets are built through neighborhoods to accommodate parked cars on both sides of the street with room for at least another car to pass through. Houses (often 3000 sq. ft. or larger) are built on lots just as large or larger than the house built on top of them, often only being occupied by a few cars and a single family, with minimum lot sizes in place to force these types of dwellings to exist.

This story is all too common across the U.S. with a reported 82 million single-family homes occupied in 2021. For the record, that’s enough homes to make up one-fourth of the U.S. population in 2021.

So, why does this matter? “Why should I care about the impact single-family residential areas have on cities?” Well, zoning of residential areas exclusively for single-family homes (as is the case with most U.S. suburban cities) helps promote exclusionary housing practices through minimum lot sizes, minimum square footage, prohibition of the building of multi-family houses, and limits on the height of buildings. In fact, more than 75% of land is set aside for single-family residential housing in the U.S.

These practices make affordable housing more difficult to achieve. A review of academic literature published by Keith Ihlanfeldt supports this, suggesting that zoning regulations increase the cost of housing in the suburbs. These zoning practices also discriminate against people of lower income and otherwise bully unwanted tenants out of neighborhoods.

In a 2016 article published by The Century Foundation, they found that supporters of exclusionary zoning actively support these policies in a bid to push out low-income residents who would lower their property values, but much evidence suggests this to be otherwise.

Discrimination is another issue that reeks at the seams of exclusionary zoning.

Although the Fair Housing Act protects people from discrimination based on race, gender, national origin, etc. towards housing with protections against things like harassment, selling and renting housing, etc., it doesn’t protect against policies like minimum lot sizes and minimum square footage prevalent in exclusionary zoning.

These policies are used to keep low-income residents out of wealthier neighborhoods majorly due to the fear of home values decreasing.

Zoning laws have made things worse with the banning of apartments in single-family residential zones through Euclid v. Ambler (1926), further contributing to the problem of a lack of affordable housing adding on top of an already broken system of exclusionary zoning.

The supreme court case, Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corporation (1977) further cemented exclusionary zoning into U.S. zoning policy, ruling that exclusionary zoning isn’t unconstitutional.

According to the Journal of Housing and Community Development, the fallout of legislation passed as a result of Euclid v. Ambler is a sharp increase in racial and economic segregation, going up by 50% between 1900 and 1940. Zoning exclusively for single-family homes also removes low-income residents from multiple opportunities such as higher-quality education and public services. Costs also decrease when zoning is less restrictive on what types of housing can be built. Instead of single-family housing only, mixed-use development can be utilized, allowing for different types of land uses to be combined on a piece of land.

Education is another issue that’s connected to making housing less affordable. Middle-class Americans living in great neighborhoods tend to be near public schools that are of higher quality, encouraging residents to protect their neighborhoods through supporting policies and propositions that encourage exclusionary zoning, in extension protecting the spot their children secured in these schools.

Frisco, Texas is a great example of this very effect. According to Zillow, the average home value in Frisco is $672,503 compared to the national average of $359,099. That’s a 60% higher average we have here in Frisco compared to nationally. If you look at the rankings of FISD in Texas and in Collin County, you’ll find that FISD ranks 12th in Texas according to a 2025 Niche ranking, and 3rd in Collin County.

It’s clear that higher property values correlate with better education as well, and the property tax rates in Frisco, which help fund public education, further support this. The state average for property tax in Texas in 2024 was $2,275 compared to Collin County’s property tax rate of $4,351.

All of this is to say despite America’s flaws in its zoning system, the system still has positive benefits as well. In a Brookings article, zoning was stated as a system that’s able to balance the needs of a city, separating industrial activity from residential homes; after all, you don’t want your house to be right next to a landfill.

On a more positive note, there’s some pushback occurring against exclusionary zoning being at the federal level through the Fair Housing Act which aims to protect people from these discriminatory zoning practices we see in exclusionary zoning.

One such way to combat exclusionary zoning is through encouraging government action, signing petitions to get laws changed to reverse exclusionary policies, and eliminating things like minimum lot sizes and minimum square footage.

Mixed-use zoning, where multiple land uses are allowed in one zone, is another way to deal with the U.S.’s broken zoning system. Not only does it lower the cost for developers to build, but also allows for opportunities to build lower-income housing in places that otherwise would have never had low-income housing.

Japan is one such place where their zoning system has succeeded. Japan’s zoning system has more flexibility allowing for housing to be built almost anywhere and in almost any form, with a few caveats of course. For example, an industrial zone in Tokyo can still contain housing as long as the factories in the industrial zone don’t jeopardize the health and safety of residents living in housing built in that zone.

While Japan may look like the epitome of what a perfect zoning system should look like, that isn’t to say cities across the U.S. haven’t made strides toward improving their zoning systems.

A mixed-use development in Plano has popped up in recent years called Legacy West, filled with shops, restaurants, and apartments. Frisco’s Railroad District is yet another example of a good starting point for better zoning incorporating developments like mixed-use development, with plans underway to redevelop part of the area, which runs through downtown Frisco.

The story of zoning in the U.S. is a complicated one filled with nuance. It’s a tough nut to crack, and there’s no exact solution that would solve all of its problems. However, one thing is for sure: the future is bright. Through the actions of the people, changes in government policies, and the willingness of developers, things can and will change.