FRISCO, TX – Student publications often face censorship from school administrations: cutting stories out of publications, editing stories to meet administrative requirements, and otherwise facing ongoing scrutiny from administrations. This leads many student journalists to craft their stories carefully, jumping through hoops set by administration to ensure their piece gets the publication it deserves.

This isn’t the first time prior review and prior restraint have been used to violate the First Amendment rights of student journalists.

We’ve seen it in court cases like Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier where stories written about students’ experiences with teen pregnancies and divorces in Hazelwood East High School’s newspaper ended up being cut by the principal, citing them as inappropriate topics, violating the student’s rights to free speech and freedom of the press as outlined in the first amendment. This, however, was overruled in the Supreme Court, where they ruled that schools didn’t violate students’ First Amendment rights when they cut out stories on subject matter seen as inappropriate.

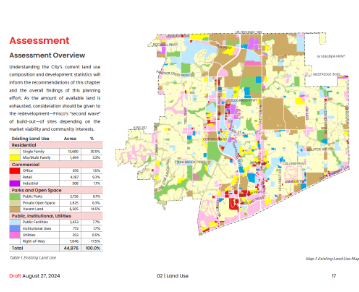

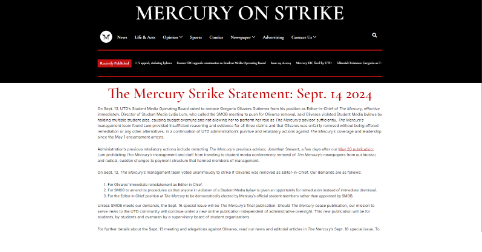

And more recently, we see examples of censorship of student publications at places like UTD (The University of Texas at Dallas), through practices like prior review and prior restraint. Prior review is when a work is reviewed by school administrators before it’s published. Prior restraint is when school administrators set guidelines for what topics can and can’t be published.

This behavior is evident in The Mercury, UTD’s student newspaper. Lydia Lum, the Director of Student Media at UTD, engaged in prior review and prior restraint of The Mercury, as summarized by Olivares Gutierrez’s rebuttal towards being removed from his position as Editor-in-Chief of The Mercury.

He went over how student publications shouldn’t be subject to prior review, a move that only serves to undermine the integrity of freedom of speech and press of such important organizations, highlighting how even industry professionals at the Dallas Morning News, when asked about navigating prior review for student publications at colleges and universities, agreed that student publications should never engage in prior review of their work by administrators.

Lum’s aggressive stance on The Mercury isn’t just a result of censoring the publication, but also a continuation of her aggressive, controlling policies towards student publications as seen in her last position at Indiana University Southeast’s student newspaper overseeing the publication.

“Lydia’s former institution and our management team alone rivals the size of The Horizon, a paper which has not published a single article since May of 2023. When Lydia left The Horizon, also in May of 2023, the publication died. The level of prior review Lydia enacted was not only ethically dubious, but it made The Horizon so reliant solely on her that when she left, publication ceased,” said Gutierrez.

This idea of pushback from school administration is further supported by the board members denying to interact with student press on the UTD campus.

“Overall, in my interactions with campus administrators since I became editor-in-chief, it became really apparent to me that they don’t want to talk to the student press,” Gutierrez said.

In addition to censorship of The Mercury, financial reasons are also used as a way for student publications to be killed by administrators as in the case of Delta State University and Northwest College where journalism programs were shut down due to “financial reasons” without further explanation as for the real cause of their closures.

Schools also seem to become upset at certain articles such as an editorial that spoke critically about Black Lives Matter at Wesleyan University, leading to threats of funding cuts to the journalism program from school administrators when that’s exactly what an editorial is supposed to do. It’s supposed to critique and argue about subject matter, and sometimes that can be controversial whether schools like it or not.

One may think that prior review is terrible for its flaws, but it still serves a grand purpose of protecting the marginalized and voiceless from harassment at the hands of these evil, wicked organizations whose only purpose is to type away at their keyboards, denouncing people who disagree with their world view or expose the deep dark secrets of how administrators have used school funds.

However, to think of prior review in that regard is the highest form of idiocracy. Prior review only serves to destroy the integrity of student publications, forcing policies that restrict freedoms that these entities deserve. Newspapers serve a crucial role in society as the messengers of breaking news and world events.

This role further extends to exposing issues like corruption and scandals. Much of that work can be seen already at the university level with school publications like Northwestern’s The Daily Northwestern, publishing a story exposing Pat Fitzgerald, then football coach of Northwestern’s football team, for allowing hazing to occur between his players with reports of alleged sexual abuses resulting from hazing incidents.

Stanford University’s newspaper The Stanford Daily is yet another example of the value of student publications through which they exposed how Marc Tessier Lavigne, then Stanford University’s president, falsified data in his research papers from 20 years ago.

So when institutions insist on implementing prior review for their journalism programs, many questions arise.

When the future news anchors and journalists are censored from doing their jobs by universities, how can these prospective professional journalists learn? If anything, the very essence of prior review and the enforcement of it is a reflection of how powerful news is and how taking control of it ultimately decides who controls opinions.

With a declining journalism industry with an ever-expanding need for new journalists to fill the ever-expanding void of the retiring, shouldn’t universities across the country bolster their support for their journalism programs?

According to a 2022 study by the University of Northwestern, they found that from 2005, one-fourth of newspapers have shut down, and an estimated one-third more are expected to shut down by 2025.

If student journalists, the future of the journalism industry, continue to be censored from diligently working to expose wrongdoings and investigate corruption scandals among other work that “goes against school guidelines,” how will journalism continue to survive as an industry?